Yesterday was the first listening event of the National Maternity Review, held at London King’s College.

The invitation, from the Chair of the review herself, Baroness Julia Cumberledge promised that the event would “…be pooling ideas to improve maternity services.”

And that “We are most anxious to hear from all those who have an interest in maternity services; the public, users, commissioners, professionals, and organisations who would like to contribute to our initial thinking. We believe there is much that is exceptional, good, kind, and sensitive to the needs of women and their families. But we also know that there are services which could improve and some which are deeply disappointing with issues that need to be addressed. At this early stage in our work, we do not have any answers but wish to hear from you and your colleagues about your experiences, your thoughts, views and opinions and some possible solutions.”

I was invited because of my work with #HugosLegacy and #MatExp. Hugo was of course present via his handprint on my necklace:

And I was keen to share to promote the post What I Want the National Maternity Review Team to Know

How did the event perform against these objectives?

Overall, very well. The room was full of a range of interested parties including consultant obstetricians, midwives, members of the Royal Colleges of Midwives and Obstetricians; various NHS organisations, members of organisations that had been set up in response to personal tragedy (such as the MAMA Academy and the Campaign for Safer Births whom I was pleased to meet but did not have enough time to talk to).

Julia Cumberledge introduced the event by outlining the scope of the review, which is looking at the maternity experience from conception through to six weeks after birth. The timescale for the review raised a chuckle…

Workstreams include choice, continuity, diversity, professionalism, culture, accountability (mutual respect between professionals and teamwork), levers (triggers and incentives) – and barriers.

The comms plan for the review includes visiting centres across the country so as many voices as possible can be heard.

I loved the ethos for the event:

Be compassionate

Be a friend

Have fun

Assume it’s possible

And so we began with the first round table discussion, looking at issues and solutions.

A few points from the discussion (facilitated by Cathy Warwick) on our table include:

- Women need individualised care within a system that genuinely supports the range and variety of experiences and needs women will have

- Polarisation – high risk/low risk and between obstetricians and midwives – is very unhelpful

- Connected with the above point, for better collaboration and teamwork between midwives and obstetricians – no ‘them’ and ‘us’. There is evidence to prove that training and working together as a team provides positive results.

- Dignified care and safe care need not be mutually exclusive (contrary to what some of the polarised debate about where is ‘best’ to give birth may suggest)

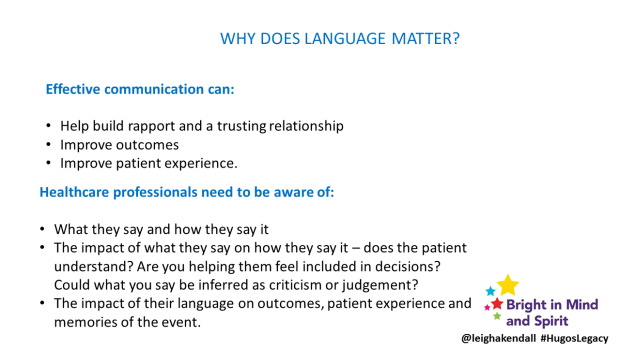

- Time for training – health professionals want to do the best they can for their patients, but are constrained by lack of time for training. Training on things like team working (such as cross over training between midwives and obstetricians so each can better understand each others’ perspectives) and effective communication would be invaluable.

- Targets – such as C-section rates – are a barrier to women receiving care that meets their own individual needs.

- Policies, procedures and guidelines are important of course, but there needs to be more encouragement for health professionals to use their own judgement to respond to women’s individual needs without fear of punitive action. This connects to issues relating to training and teamwork – enabling staff to do their jobs and giving them confidence in their practise – in short, empowering them to do their best.

Feedback from the other tables was insightful, including this point that being part of #HugosLegacy was music to my ears…

There needs to be a seamless care pathway to better meet the needs of mums whose babies are in the neonatal unit, as described in my post about what I want the review team to know.

Other points of insight included:

- Need to make sure good practice can be shared across hospitals

- Need to find ways to make sure care is women-centred – this goes back to tick boxes and things like C-section targets.

- Need for better postnatal care.

- Need for commissioning that is better connected between CCGs, local authorities, and NHS England.

- Need to look at culture – acceptance that innovative vision is the way forward to make the changes that need to happen.

- We need to manage risk, risk should not manage us. Antenatal education needs to empower women to make the right choice for them.

- We need to eradicate concept of ‘high risk/low risk’.

- Women and their families need to be more involved in the creation of pathways

- Evaluation methods need to be more useful for service users – and the feedback meaningful.

- A woman needs to be seen as a whole person, not a womb with legs – her emotional and psychological needs, for example, need to be considered too.

Three crucial concepts are: language, behaviour, and leadership.

(This is not an exhaustive list, and I may have missed things!)

There are a few issues that bear further exploration, for example: the remit of the review includes experiences up to six weeks after birth. This has the potential to miss two crucial issues: postnatal mental health, and the needs of mothers whose babies are in neonatal care, and/or who suffer a loss. The needs of these women extend well beyond the six week timeframe, and have long-lasting, serious consequences if those needs are not met.

I would be interested to see how the review incorporates these issues.

From a personal point of view, the event gave me a wonderful opportunity to catch up with and meet fantastic people whom I have got to know through social media. I won’t try to name everyone because I usually end up missing people out, but here are some photos…

Flo and I managed to stop talking long enough to take a photo

I loved seeing Alison Baum again (she’s CEO of Best Beginnings, creator of the DVDs for which people so generously donated money for Hugo’s first birthday) and meeting Heidi, founder of the MAMA Academy, of which I am proud to be an ambassador.

Meeting and having a chat with Jacque was fab

Gill and I enjoyed a lovely evening chatting. We forgot to get a selfie, but I have a picture of my pink shoe on my pink bag…

Flo took a JFDI #MatExp view to sharing the campaign, with one of the brilliant graphics and giving people an overview of the Whose Shoes game.

I may be biased, but the innovative, grassroots, no-hierarchy approach of #MatExp is key to the success of the review. It is heartening to see there is interest:

The event nearly ended in tears for me, however. Chatting about #MatExp to two ladies at the end of the event led to me sharing my own experience. Asking how long Hugo lived for (35 days), they commented that it was ‘quite a long time’. I disagreed, saying that it was not nearly long enough. Objectively, I know that as Hugo was born at just 24 weeks the fact I got any time with him at all was miraculous, and I am very grateful for every precious moment I had.

But a tip for others when talking to a bereaved mother: DO NOT try to tell the mother that they are in any way ‘lucky’, and especially DO NOT persist in your point of view once the mother has expressed upset.

The women did apologise, saying it’s difficult to know what to say to bereaved parents. Another tip: empathy is key. ASK the parent how they feel, and if you really don’t know what to say, STOP TALKING.

Considering the breadth of experience of women – and men – attending these events will have, taking a moment to consider sensitivity, as well as sensible things to say (and not say!) is crucial.

Fortunately, it did not mar the very constructive and productive day. I hope we can see our thinking translated into real action and change for women and the staff who care for them.

Next steps are…

and if you want to be involved…